Checkmate for Barrick Gold

ARGENTINA’S SUPREME COURT UPHOLDS GLACIER PROTECTION LAW

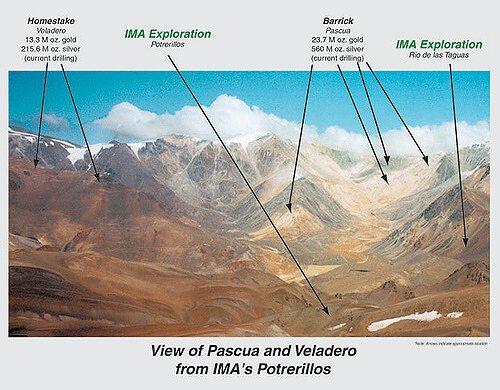

Straddling the high peaks of the southern Andes, the Canadian mining giant Barrick Gold’s $5Bn. Pascua Lama project, one of the company’s most controversial open-cast mining operations, looms menacingly over Argentina and Chile. The project, covering 2,600km2 between the two countries, will not only endanger the water sources feeding them, but will also alter the topography of the great Andean mountain range that runs down the spine of western South America.

Back in 2009 Pascua Lama was heralded as a ”world wonder”, given its reported extractive potential when it goes into production in early 2013:18 million ounces of gold over a 25 year period.* It is, however, a complex operation. For example, rocks will be crushed in Chile and processed in Argentina, with the latter supplying the bulk of the water at a rate of approximately 75 million litres per day. The water issue is one of the most crucial in the controversy that has surrounded Pascua Lama and is the underlying purpose of Argentina’s Glacier Protection Law.

The Glacier Protection Law passed on the 29th of September, 2010 was intended to protect the glaciers as a key source of water reserves. To that end it bans mining and oil drilling on glaciers and periglacial areas. (Periglacial refers to areas where the ice has recently retreated, but water remains below the surface. The glaciers and periglacial areas provide much of Argentina’s fresh water.) The Glacier Protection Law also requires the national government to define a glacier and to inventory the remaining glacial and periglacial areas throughout the country. Furthermore, it requires the mining companies to provide environmental impact assesment statements at the national level. Already during the congressional discussions preceding the passing of the law several mining provinces, notably the province of San Juan, raised strenuous objections, claiming that provincial governments have the constitutional power to manage their own natural resources. One of the most outspoken critics of the law was the Senator for San Juan, César Gioja, whose company provides Barrick Gold with supplies for drilling operations.

On the 8th of November, 2010 a federal judge of San Juan, Miguel Angel Gálvez, suspended the application of six articles of the law following a request by the provincial government, and the mining companies Barrick Exploraciones Argentina S.A., Minera Argentina Gold S.A. and Exploraciones Mineras Argentinas. All three companies argued for the suspension of the law for their mining projects Veladero and Pascua Lama, both of which are sited in San Juan.

In a landmark ruling on the 3rd of June, 2012, Argentina’s Supreme Court reversed Judge Gálvez’s decision, thus handing the Argentine government legal powers to regulate the country’s mining industry which, unlike the mining industries of Chile and Peru, is still underdeveloped,.

Whether or not the government of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner uses these regulatory powers remains to be seen. Given the rapidly worsening economic situation in Argentina, it is difficult to see how the government can afford to antagonise powerful mining companies like Barrick by stepping in to regulate an industry which until now has been handled by provincial governments.

On this score President Kirchner has an ambiguous track record. In 2008 she vetoed a similar law, claiming that it would endanger provincial economies. In 2010 the opposition parties in Congress approved a draft bill of the Glacial Protection Law by a 129 to 86 majority, despite the government and the mining companies having requested a fifteen-day postponement. The President said she would abide by the congressional decision and signed the bill into law. Since then the government has gradually started to compile an inventory of periglacial areas, but after two years only one area in the province of Mendoza has been inventoried.

Local environmentalists, such as the environmental advocacy group CEDHA, say Earth images show glacial ice in other mine sites. In particular they name Barrick’s Pascua Lama and two copper-mine projects: Xstrata’s El Pachon and McEwen Mining’s Los Azules. Daniel Talliant, founder of CEDHA, believes that as more periglacial areas are found, mining will cease.

Not surprisingly, Barrick denies that it is mining glaciers and periglacial areas. Yet while it insists that it carries out environmental impact assessment statements, so far it has been able to block legal requirements that it provide the national government with those statements. In the words of the company’s vice president for corporate affairs in South America, ”We believe we are legally entitled to continue our current activities on the basis of existing approvals.” He adds that the federal legislation, ”also draws a distinction between new projects and those already underway. Our Veladero mine has been in operation since 2005 and construction at Pascua Lama has been underway since 2009.” Coincidentally (or not, as the case may be) the Veladero mine, which is near the Pascua Lama project, is sited in San Juan province where the federal judge suspended the six articles of the Glacier Protection Law in 2010.

Barrick says it is ”evaluating” the Supreme Court decision. For now the result of that evaluation is anyone’s guess, but it seems reasonable to believe that the company will put up a strong fight to get its way. Along with other transnational mining companies, it rejects the idea that a national government should have any hand in regulating the industry. And Pascua Lama’s potential 18 million ounces of gold is too glittering a prize to let slip through its fingers. Environmental destruction due to mining is low on the company’s list of priorities. So is the opposition by local communities faced with depletion of their water supply and an impending ecological disaster, as well as serious health hazards for people and animals due to pollution by toxic mining waste. In the end, Barrick will undoubtedly play its ”might is right for business” card and strongarm an economically and politically weak government into finding a way around the Supreme Court’s ruling.

The people who will suffer most from Barrick’s ”might is right for business” philosophy are those local communities that lie within the range of Pascua Lama’s activities on both sides of the Argentine-Chilean border. It is their homes, lives and livelihoods that will bear the brunt of the mining operation. But ultimately it is the women, children and the elderly of those communities who are most vulnerable and at the greatest risk.

* Map generated by IMA (Kobex Minerals Inc) financed by Barrick Gold for exploration of Barrick’s Pascua Lama and Veladero properties in San Juan has 23,7 million oz. gold and 560 million oz. silver. (source, No a la Mina article, Amparos inversamente proporcionales a la masa glaciar, 09/11/2010)

Check these out

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino Non Aams

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Casino Non AAMS

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Online Casino Uae

- Beste Online Casino

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Gambling Not On Gamstop

- Migliori Siti Casino Non Aams

- Casino Sites UK

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Slots Not On Gamstop

- Casino Online Migliori

- Casino Online Italia

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Meilleur Casino Belgique En Ligne

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Siti Scommesse Aams Nuovi

- Casino En Ligne

- Bookmaker Crypto

- Online Casino Malaysia

- カジノアプリ 稼げる

- オンライン カジノ ブック メーカー

- Site Casino En Ligne

- Migliori Casino Non Aams

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat 2026